Survey conducted by a team of Rohingya women and led by Ro Abdullah

Design: Abdullah Ibrahim

Copy Edit: Dr. Kathy Bullock

Special thanks to Adam Carroll

ISBN: 978-1-960709-15-8

Copyright © 2025 Justice For All

All rights reserved.

Executive Summary

Food

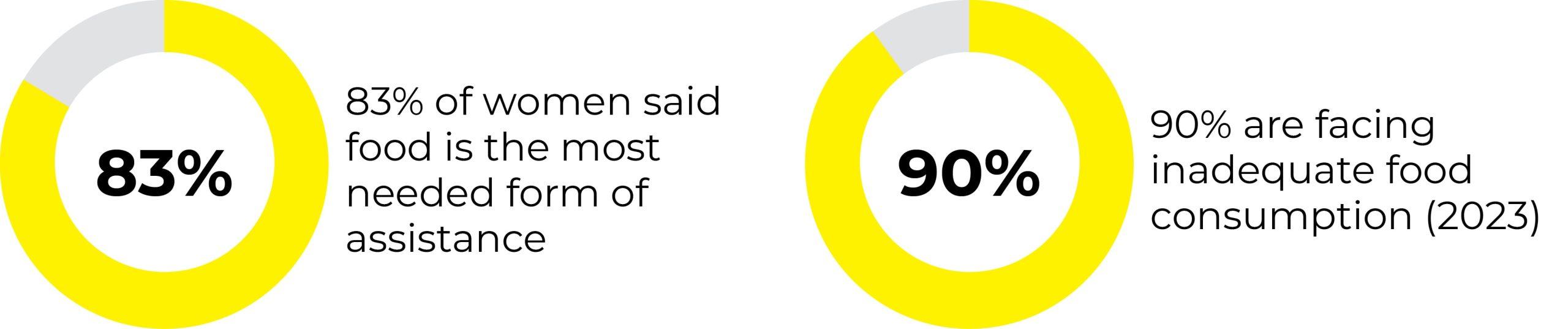

- Food Assistance: Almost 83 percent of respondents prioritized food as the assistance most needed in the camps.

- Insufficient Rations: Women reported being unable to meet the basic needs of their family due to insufficient monthly rations.

- Impact of Funding Cuts: Food insecurity worsened after World Food Programme funding cuts and the recent suspension of USAID.

- Lack of Non-Food Items: Women reported a lack of non-food items, including clothing and hygiene products.

- Inability to Pay Dowry: Women reported concern over inability to afford dowry for their daughters, a cultural practice forcing women into desperate situations.

- Challenges Collecting Aid as a Woman: Women without a male relative reported feeling unsafe and vulnerable when trying to collect aid.

Education

- Barriers to Education: The Rohingya community remains reliant on religious education (madrasas) to provide religious instruction, fundamental literacy and numeracy skills. Access to quality education is severely restricted as Rohingya students are barred from attending institutions outside the camps.

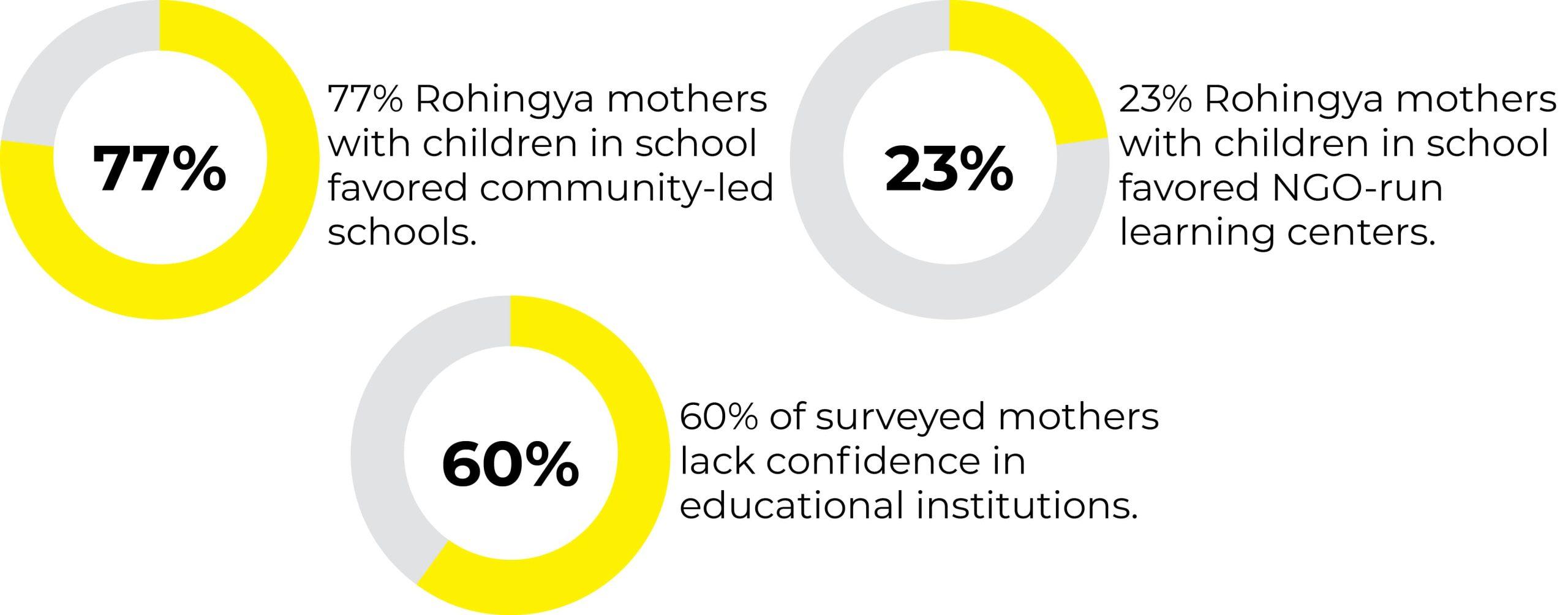

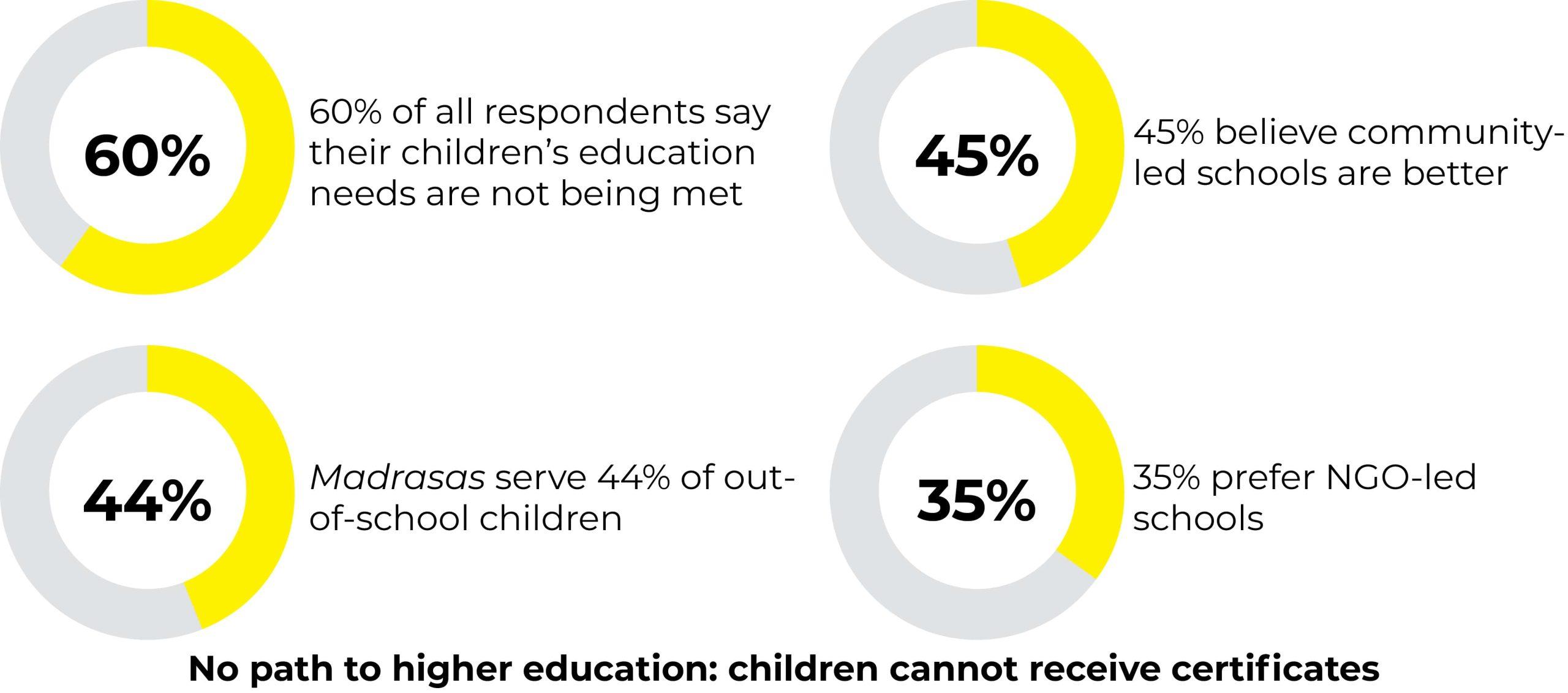

- Perceptions of Education Quality in NGO and Community-Led Schools: An overwhelming majority of Rohingya mothers with children in school favored community-led schools (77 percent) compared to NGO-run learning centers (23 percent). Despite the preference expressed, over 60 percent of surveyed mothers lack confidence in the quality of education and shared concerns about their childrens’ future prospects.

- Key Concerns in NGO and Community-Led Schools: Mothers highlighted key concerns including the lack of pathways to higher education, limited curriculum, low quality teaching, issues accessing school consistently, resource constraints and cultural relevance.

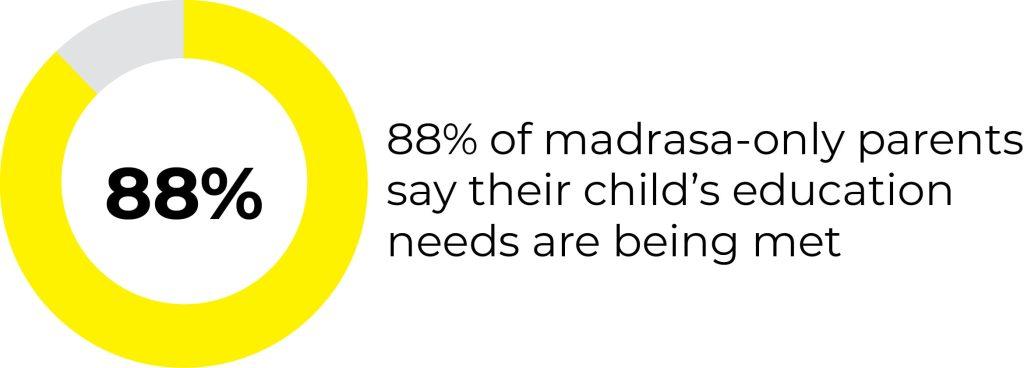

- Madrasa-Only Parents Are Generally Content: Eighty-eight percent of parents whose children only attend madrasas answered that their children’s educational needs are being met.

- Education for Rohingya Women: Respondents emphasized the lack of educational opportunities available for women, as well as limited and outdated skills programs. They sought women-only madrasas.

- Role of Wives of Imams and Female Scholars: Wives of imams and female scholars play an important role in the Rohingya community in educating, counseling and advocating for other women.

Security

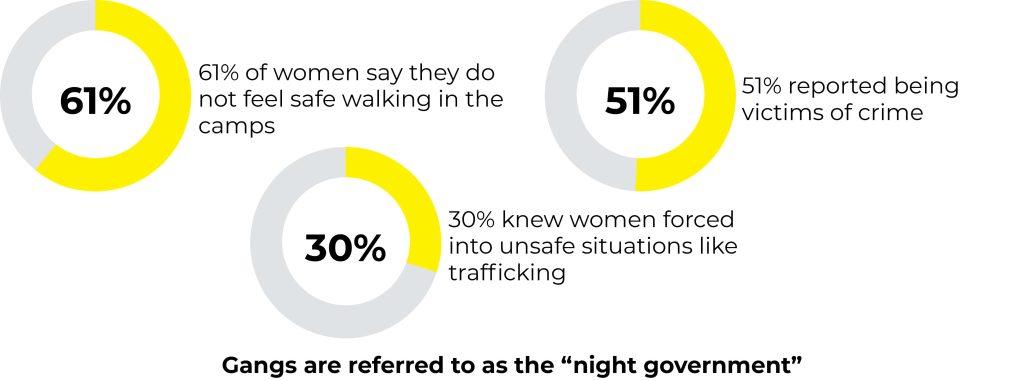

- Safety is Lacking in the Camps: Sixty-one percent of survey respondents did not feel safe walking in the camps. Fifty-one percent of respondents reported being victims of crimes such as robbery. Thirty percent of women reported being aware of cases of women forced into unsafe situations, such as sexual exploitation and forced labor. Safety was mentioned as a concern no matter the marital status.

- Gang Recruitment, Kidnapping, and Threats: Interviewees reported kidnappings of their husbands and children, who were held at ransom. Women also reported their husbands being threatened and compelled to go into hiding due to forced recruitment efforts by gangs and armed groups.

- Forced Marriages and Human Trafficking: Women shared stories of being trafficked to Indonesia, India and other countries.

- Safety Concerns in Using Sanitation Facilities: Women reported avoiding toilets, particularly at night with inadequate lighting, due to heightened risks of harassment and assault.

- Heightened Vulnerabilities for Women without Mahram (male family member): Women without a male relative face heightened susceptibility to gender-based violence, exploitation and harassment.

- No Legal Recourse After Falling Victim to Crime: Interviewees expressed distrust in police forces, suspecting police complicity in crimes committed by gangs and armed resistance groups. Fear of retaliation and further abductions leads many to withhold their identities.

Introduction

Rohingya: “The Most Persecuted Minority in the World”

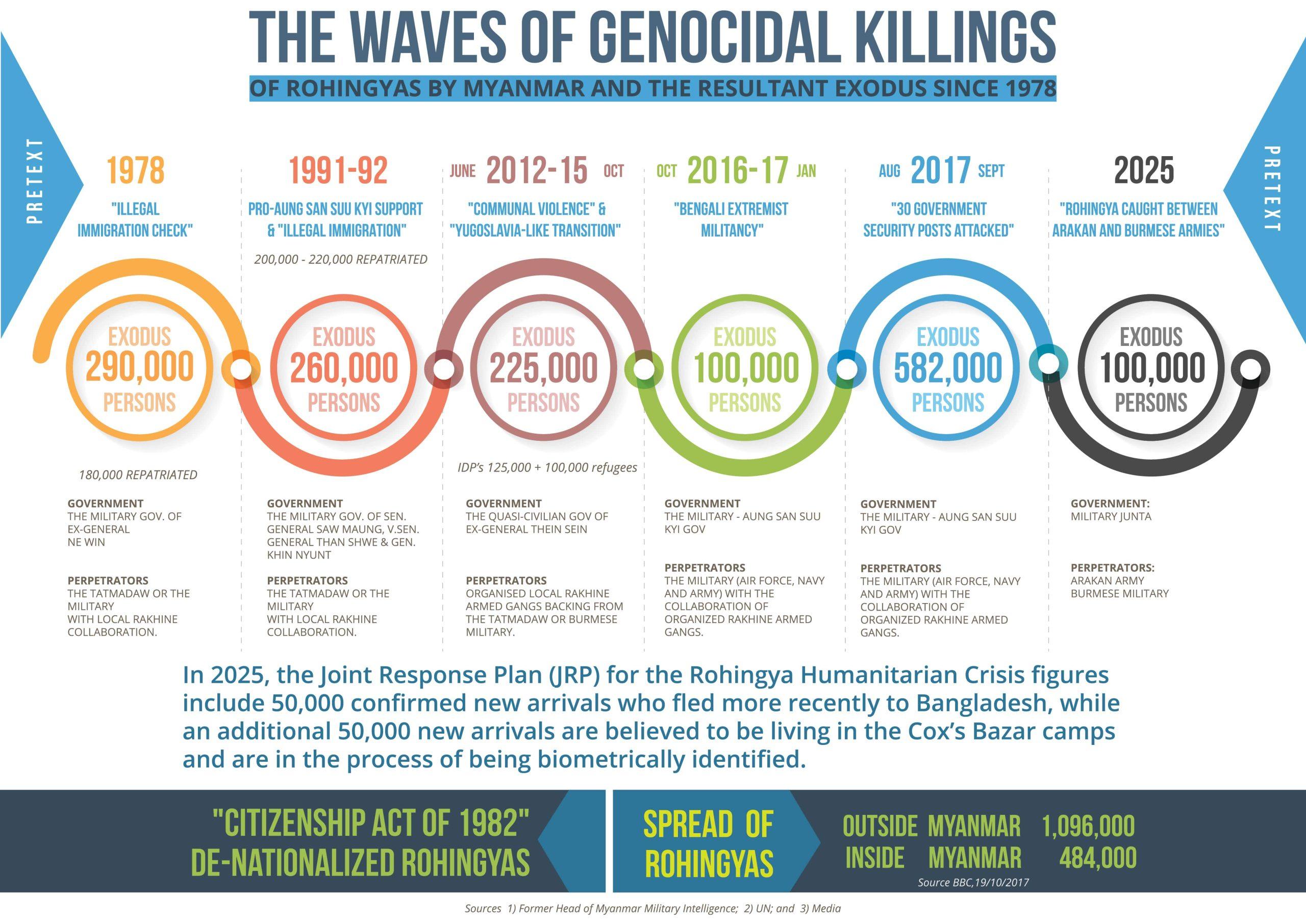

The United Nations has described the Rohingya as “the most persecuted minority in the world.” The Rohingya are an ethno-religious minority group who lived for many generations in Burma. (We follow the Burmese diaspora in continuing to call the country “Burma,” not accepting the name “Myanmar” that the military government imposed in 1989.) Historically, Rohingya have been subjected to systemic discrimination, statelessness and violence. Since 1982, they have been denied citizenship and basic rights, making them the world’s largest stateless population.

In August 2017, genocidal violence in Burma’s Rakhine State caused over 700,000 Rohingya to flee, with 600,000 entering Bangladesh. This surge of forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals added to earlier inflows, bringing the current number of Rohingya living in Cox’s Bazar to over one million. New arrivals set up makeshift camps around the previously registered ones, now comprising Kutupalong, the largest refugee camp in the world. In 2020, UNHCR and the Government of Bangladesh implemented a joint registration process to consolidate data for the Rohingya population and issue documentation for refugees. The Government of Bangladesh refers to Rohingya as “Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals,” (FDMN), while the U.N. system refers to them as “refugees” under the applicable international framework. We use these two terms interchangeably in this report to refer to the same population.

The purpose of this report is to provide a comprehensive update on the status of Rohingya women living in the refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, after they were forced out of Burma in 2017 and arrived in Bangladesh. The report is based on a survey of 1000 Rohingya women, augmented by a Justice For All delegation visit to the camps to conduct interviews in December 2024. This report focuses on three areas: food, education and security. A subsequent report will focus on the other areas explored in our survey and interviews: healthcare, employment and privacy.

According to the World Bank, women’s empowerment and gender-based violence outcomes are among the least explored in the context of humanitarian assistance programs. This underscores the critical need for focused research and targeted interventions to address these gaps. By shedding light on these underexplored areas as well as the areas of concern indicated by Rohingya women in the camps, our report aims to inform and enhance policy and programmatic responses to better support Rohingya women in these camps.

This report begins with an overview of the general situation in the camps, followed by a section describing our research methodology. Chapter One focuses on food, Chapter Two on security and Chapter Three on education. Each chapter begins with a general overview of the focused issue under examination, followed by results and discussion from our survey and field research.

Kutupalong: The World’s Largest Refugee Camp

Over 1 million Rohingya are concentrated in the Kutupalong camps in Cox’s Bazar region in Bangladesh, the world’s largest refugee camp, where they live in overcrowded and unsafe conditions. This is bigger than Austin, Texas, or similar to the population of Ottawa in Canada. The Kutupalong camps are made up of 34 different camps. Families live in makeshift shelters constructed with tarpaulin, brick, bamboo, mud and plastic sheets (which have poor ventilation and become extremely hot). Living in open shelters, they are exposed to weather-related hazards, such as storms, floods and landslides; they are vulnerable to rampant violence, exploitation and criminal activity by gangs. In Cox’s Bazar’s refugee camps, 95 percent of Rohingya households depend on humanitarian aid, with more than 75 percent of the population being women and children. There is no running water, electricity or internet. They rely upon intermittent and independent electricity sources like solar panels. For cooking, LPG is the primary fuel used; cylinders are funded by NGOs and the Bangladeshi government, and require refill assistance every 30-45 days. Due to restrictions and shortages of LPG, refugees often revert to using fuelwood (wood, sawdust, pellets and the like) for cooking. Safe drinking water is delivered to the camps in the form of tubewell handpumps. Sanitation facilities include bathing, handwashing and latrine stations, many of which are located in areas prone to flooding or landslides, which presents risks to health and water security. The arrangements were intended for temporary use, but at time of writing, Rohingya refugees continue to live here with no certainty of return to their homeland.

Lack of Legal Recognition

Though native to Burma, the Rohingya have been rendered stateless. Practically, this means they are unable to obtain identification documents or passports, leaving no safe or legal pathway for them to seek asylum. Consequently, they are forced to undergo perilous journeys, often facilitated by human traffickers, facing violence, extortion, sexual assault or even death along their journeys.

Upon reaching Bangladesh’s camps, the Rohingya are not legally recognized as “refugees,” though they fall under the definition. As Bangladesh is not a party to the U.N. Refugee Convention and Protocol, the government maintains that to recognize the Rohingya as “refugees” would suggest permanence, enticing more to come with the expectation of resettlement. So the government refers to the Rohingya officially as Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals.

The Rohingya are not permitted to leave the camps either. Military and police checkpoints control access to and from the camps. Even within the camps, interviewees noted they are no longer freely permitted to move from one camp to another. With no legal status in Bangladesh, Rohingya refugees face severe limitations on access to employment, education, healthcare, essential services and protection. Lack of refugee status also makes it difficult for Rohingya to access education, health care, justice and resettlement options in other countries.

Rising insecurity in the Bangladesh camps has forced many Rohingya to once again undertake perilous journeys by sea, risking their lives aboard overcrowded smuggler boats bound for Indonesia. These sea routes, described by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as among the deadliest in the world, have claimed countless lives. In 2023 alone, an estimated one Rohingya refugee died or went missing for every eight who attempted the journey. Since November 2023, nearly 2,000 Rohingya refugees have arrived in Indonesia by boat, highlighting the desperation driving these dangerous migrations.

Governance in the Camps

Governance in the Rohingya camps is made up of several overlapping institutions each responsible for different aspects of life there: (i) The Government of Bangladesh, which includes the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief (MoDMR), Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commission (RRRC), Camp-in-Charge (CiC), the army and the police; (ii) humanitarian actors, including the U.N., nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations (CSOs), a Site Management Sector; and (iii) local community leaders.

The Ministry of Disaster Management (MoDMR) is responsible for disaster relief and the refugee response, including governance of the camps, and manages the Relief Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commission (RRRC). The RRRC is the government body responsible for the refugee population, for management and appointment of Camp-in-Charge (CiCs) on a rotational basis, and is the primary contact with U.N. agencies. The Bangladesh army oversees many aspects of disaster management, including road construction, and operationalizing the biometric registration that was run by the Ministry of Home Affairs on behalf of the Government of Bangladesh, together with UNHCR. The police are responsible for safety and security in the camps.

The CiCs are the government representative responsible for administering and coordinating services in the camps, liaising with governments and the U.N., and making decisions over every actor in the camp. They are accountable to the RRRC.

Bangladeshi government and CiC policies are administered in the camps via a system of government appointed Rohingya leaders, known as majhis. Rather than the community electing their own representatives, these government-appointed majhis not only enforce Bangladeshi policies, they also represent the Rohingya in matters such as settling community disputes and aid distribution. They report to the Bangladeshi CiCs. The majhis serve as the primary resource for camp residents to obtain information and resolve issues. However, because of the disproportionate concentration of power in the majhis as the sole representative of Rohingya refugees in the camps and the fact that they are unelected, a 2019 survey found that one-third of Rohingya have “little to no trust” in majhis. The majhis are unpaid. According to refugees and humanitarian actors, some majhis have charged rent to camp residents illegally. The Bangladeshi government allowed the UNHCR to implement an election system in four of the 34 camps, but the government is reluctant to change the system of appointing the leaders.

The humanitarian actors involved include U.N. agencies, such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the World Food Programme (WFP), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), U.N. Women, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The Bangladeshi Relief Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commission (RRRC) and the U.N.’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) co-lead the site management sector, to ensure site management response is coordinated. UNHCR and IOM have split the camps for site management.

There are numerous NGOs providing humanitarian assistance, including Bdesh Foundation, Education Development and Services (EDAS) and BRAC. They are active in many aspects of charitable relief, such as childcare, education, safety for women, and basic needs like shelter, food, water and clothing.

Local community leaders are volunteers who are elected to serve a six to twelve month term on camp-level governance structures, which are camp and block committees. They are responsible for facilitating humanitarian assistance by engaging with the community. The CiC and NGOs also engage with other volunteers in the camps in order to support the humanitarian assistance. Some receive a small compensation of 50 Bangladesh Taka/hour (about $USD 0.47) for their service.

Religious leaders hold positions of unofficial influence over the community due to their knowledge and status as an educator. In contrast to the distrust placed in the majhis, a survey conducted by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) found that 99.5 percent of surveyed Rohingya had “complete trust in the religious leaders-imams in the camps.” In addition to imams, there are masjid committees (mosque committees), which convene to make decisions around Islamic law. While there are some women, the majority are men.

Lack of Legal Recognition

Though native to Burma, the Rohingya have been rendered stateless. Practically, this means they are unable to obtain identification documents or passports, leaving no safe or legal pathway for them to seek asylum. Consequently, they are forced to undergo perilous journeys, often facilitated by human traffickers, facing violence, extortion, sexual assault or even death along their journeys.

Upon reaching Bangladesh’s camps, the Rohingya are not legally recognized as “refugees,” though they fall under the definition. As Bangladesh is not a party to the U.N. Refugee Convention and Protocol, the government maintains that to recognize the Rohingya as “refugees” would suggest permanence, enticing more to come with the expectation of resettlement. So the government refers to the Rohingya officially as Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals.

The Rohingya are not permitted to leave the camps either. Military and police checkpoints control access to and from the camps. Even within the camps, interviewees noted they are no longer freely permitted to move from one camp to another. With no legal status in Bangladesh, Rohingya refugees face severe limitations on access to employment, education, healthcare, essential services and protection. Lack of refugee status also makes it difficult for Rohingya to access education, health care, justice and resettlement options in other countries.

Rising insecurity in the Bangladesh camps has forced many Rohingya to once again undertake perilous journeys by sea, risking their lives aboard overcrowded smuggler boats bound for Indonesia. These sea routes, described by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as among the deadliest in the world, have claimed countless lives. In 2023 alone, an estimated one Rohingya refugee died or went missing for every eight who attempted the journey. Since November 2023, nearly 2,000 Rohingya refugees have arrived in Indonesia by boat, highlighting the desperation driving these dangerous migrations.

Role of Donor Countries, U.N. Agencies and Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs)

Bangladesh has taken on the significant responsibility as the host country of over a million Rohingya refugees. They are supported by donor countries, U.N. agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and civil society organizations (CSOs), each playing distinct but complementary roles in addressing the humanitarian crisis.

Donor countries provide financial assistance that supports the operational efforts of U.N. agencies and international NGOs. The United States used to be the largest donor, contributing $301 million in 2024, which accounted for approximately 55 percent of all foreign aid for the Rohingya refugee population. This aid was primarily for food and nutrition through USAID (through the Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance) and the State Department (through the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration). Though USAID was required to facilitate the transition from providing humanitarian assistance to development assistance, they faced obstacles, such as the restrictions imposed by the Bangladesh government on activities, infrastructure, and access that suggest permanence of the Rohingya, as well as growing social tensions between the Rohingya and locals. The current Trump administration has temporarily suspended USAID to Rohingya refugees, exacerbating an already dire humanitarian situation in Bangladesh.

Here is a breakdown of what some of the U.N. agencies provide in the Rohingya camps:

- The U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR): provides emergency life-saving aid, including blankets, plastic sheets, sleeping mats, family tents, plastic rolls, kitchen sets, jerry cans and buckets; helps the Bangladesh government develop new sites to safely accommodate refugees; builds and improves latrines and water points; and provides support for survivors of gender-based violence and at-risk children.

- The United Children’s Fund (UNICEF): works with the Bangladesh government to provide disaster relief to children and families living in the camps, focused on providing water, sanitation, health services to address rising malnutrition and preventable diseases, child protection through youth centers and gender-based violence risk mitigation, and education by supporting 4,200 learning centers and training volunteer teachers. (As of the printing of this report all learning centers have been closed.)

- World Food Programme (WFP): provides fresh food assistance and implements nutrition programmes for pregnant and breastfeeding women and children under five years of age.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM): leads climate-resilient solutions, such as bamboo treatment to lengthen the bamboo’s lifespan used to build shelters, and solar-powered water treatment and distribution facilities; provides alternative fuel sources; supports 38 healthcare centers; provides access to latrines and clean water; provides support to help Rohingya refugees maintain their identity and culture, and protect refugees from gender-based violence, human trafficking and child abuse.

- Education Cannot Wait (ECW): provides learning materials, teacher/administrator training, learning spaces; advocates for use of the Myanmar curriculum, which is being scaled up; addresses barriers to education for women and girls; and prioritizes inclusion of children with disabilities.

NGOs work with U.N. agencies to provide additional operational support, such as BDesh Foundation, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and World Vision, among many others. For example, BDesh Foundation responded on the ground to burn victims in a fire, and has initiatives such as Project Women Care and Child Care Centers to support women and children.

United States and Canada Name a Rohingya Genocide

United States

On December 13, 2018, a Republican-led Congress passed a resolution declaring that the “atrocities committed against the Rohingya by the Burmese military and security forces since August 2017 constitute crimes against humanity and genocide[.]” Four years later, on March 21, 2022, the United States formally recognized the atrocities committed by members of the Burmese military against the Rohingya as genocide and crimes against humanity. Furthermore, the United States has supported efforts to hold persecutors responsible, including providing $1 million to the U.N.’s Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar to collect evidence, backing the Gambia’s case against Burma before the International Court of Justice, and imposing financial sanctions on Burmese individuals involved in abuses and enterprises related to the Burmese military. The United States has also committed to providing life-saving humanitarian assistance to Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, sending over $1.7 billion since August 2017. The recent decision by the Trump administration to freeze foreign aid has marked a sad departure from this positive legacy.

Canada

Since 2017, when Canada formally appointed a Special Envoy for Myanmar, Ambassador Bob Rae, Canada distinguished itself as one of the global leaders addressing the Rohingya genocide. In 2018, the Canadian House of Commons recognized the atrocities against the Rohingya as a genocide. That same year, Canada revoked Nobel Peace Prize winner (1991) Aung San Suu Kyi’s honorary Canadian citizenship. In 2023 Canada joined as an intervener in support of The Gambia’s case against Burma (Myanmar) at the ICJ.

However in recent years, Canada’s efforts toward the Rohingya have diminished as priorities have shifted. For example, at time of writing, Canada had not yet renewed its multi-year strategy to address the crisis, and has simultaneously reduced aid, exacerbating the already dire humanitarian situation. Canada committed $300 million dollars of funding from 2018-2021 and $288 million from 2021-2024, but no support has been committed in the recent budget. We will have to see what the new Prime Minister, Mark Carney, elected on April 28, 2025, does on this file.

Survey Methodology

This report is based on a survey of 1,000 Rohingya women living in the camps, developed by Justice For All’s Burma Task Force and administered between November and December 2024, augmented by a field visit to the Kutupalong camps in December 2024 by a Justice For All delegation consisting of seven staff and volunteers. The delegation engaged directly with refugee women who had participated in the survey and who had agreed to share further personal testimonies. These interviews provide additional insights into the lived experience of Rohingya women in the camps, offering a more nuanced perspective on the specific obstacles they face. This report focuses on their views on food, education and security. A subsequent report will include some of their testimonies on the other areas explored in our survey and interviews: healthcare, employment and privacy.

The survey of 1,000 Rohingya women was conducted under the supervision of an appointed Project Manager in the Rohingya camps in Bangladesh. Approximately five Rohingya women, each with prior experience in primary research, were selected to conduct the survey. Names are omitted for safety reasons.

The Justice For All delegation that visited the Rohingya camps in Bangladesh in December 2024 strictly adhered to principles of independence, impartiality and objectivity, taking care to obtain consent before taking any photos, videos or notes. The delegation further considered safety concerns with regards to sharing information about those currently facing threats of violence from gangs or other threats to their safety.

Participant Selection:

To ensure a representative sample, surveyors employed a systematic approach by selecting every tenth dwelling within the camps. At each dwelling, a female household member aged 18 or older was invited to participate. In instances where the selected dwelling was unavailable (e.g., no one was home, or the individual did not meet the criteria), the interviewer would skip to the next dwelling in the sequence.

Language and Data Collection:

Recognizing the linguistic needs of the respondents, the survey was translated from English to Rohingya by the interviewers. Responses were then recorded in English for consistency and ease of analysis.

Data Compilation and Analysis:

All collected data was entered into Kobo Toolbox, a mobile data collection platform that the survey team is familiar with. This platform allowed for efficient data entry, monitoring and analysis.

Ethical Considerations:

To ensure the integrity and ethical rigor of the survey, all interviewers were trained on ethical research practices. Additionally, they were encouraged to complete the “Ethics in Interviewing” certification available through the Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS2).

Respondent Demographics

The Rohingya women who were surveyed consisted of the following demographics:

- Age:

- 16-24 (37.5 percent)

- 25-34 (29.3 percent)

- 35-44 (15.4 percent)

- 45-54 (8.2 percent)

- 55+ (3.3 percent)

- Unspecified (6.1 percent)

- Marital Status:

- Married (59.3 percent)

- Single (Never Married) (25.6 percent)

- Widowed (8.6 percent)

- Divorced (6.3 percent)

- Unspecified (0.02 percent)

- Children:

- Have children (68.6 percent)

- No children (24.7 percent)

- Unspecified (6.7 percent)

Chapter One: Food

Background

The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), which is funded through voluntary contributions, is the entity responsible for providing food assistance to Rohingya refugees. In the past, food assistance in the camps was provided in two forms: general food distribution (GFD) and electronic vouchers (e-vouchers). Households selected for GFD would receive rice, lentils and cooking oil at designated distribution points, with the size of the ration and frequency of payment depending on household size. Households selected for the e-voucher would receive a card similar to a debit card with an electronic chip that allows for monthly payment to be made remotely without refugees needing to go to a physical location to receive payment. The selection at the time as to whether a household received GFD or an e-voucher was not based on a formal process, but rather on the availability of land granted by the Bangladesh government for new shops to be constructed, with households near the shops receiving e-vouchers.

Food Assistance: Transition to the E-Voucher System

The WFP implemented the e-voucher system in 2017 to provide refugees with more autonomy over their food choices and stimulate the local economy. E-vouchers can only be used at designated vendors within the camps, many of whom are Bangladeshi-owned businesses that operate under WFP contracts. The vendors supply a range of eight to ten essential food items, including rice, lentils, oil and onions at “food corners.” A 2018 survey showed that receipt of an e-voucher was associated with improved linear growth of children between six and 23 months old, the age range considered critical for child nutrition. By 2021, the WFP had scaled up to nearly all Rohingya refugees, and now all Rohingya refugees receive e-vouchers.

Recent Developments: Impact of Funding Cuts on Food Security

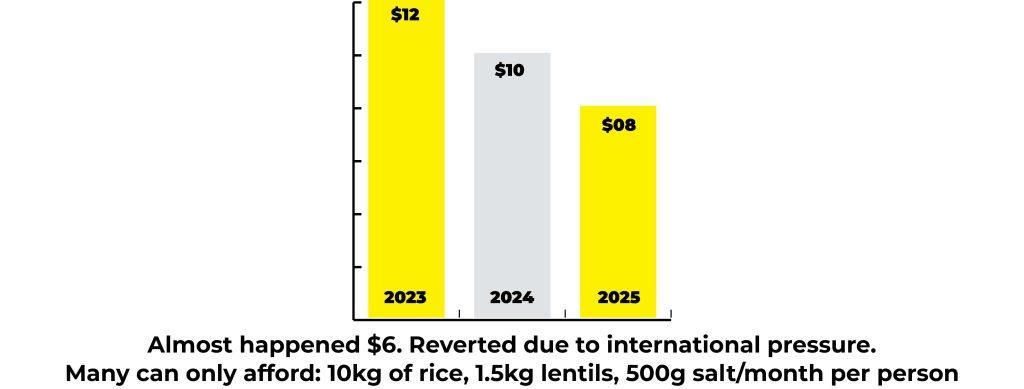

In 2023, acute funding shortages had forced the WFP to cut food assistance for the Rohingya from $12 to $10, and then $8 per person per month, worsening food security, with 90 percent facing inadequate consumption. USAID had come to the rescue in December 2023 with $87 million in assistance, and then another $121 million in November 2024.

In early March 2025, due to funding shortfalls, WFP announced it would again be forced to reduce the food voucher for Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar by half, from $12.50 (USD) to $6 per person per month. WFP later reversed this decision on March 27, 2025, confirming that, despite funding shortages, it would allocate $12 per person per month in Cox’s Bazar to help ensure the nutritional needs of the Rohingya are met.

The recent suspension of USAID funding, following President Trump’s Executive Order 14169 on January 20, 2025, has had immediate and severe consequences for food security in the Rohingya refugee camps. Rohingya refugees stated that at current costs, the voucher is only enough to buy 10kg of rice, 1.5kg of lentils and 500g of salt. While the WFP has been permitted to continue distributing rice, this permission does not extend to supplies to boil and cook the rice, including fuel and cooking oil. Rohingya refugees were “barely surviving” with the existing monthly food rations, according to the RRRC of Bangladesh, and if rations were to be cut further, it would have a devastating impact on refugee health, nutrition and safety – particularly for women and children, who make up 78 percent of the population. Moreover, according to Daniel Sullivan, the director for Africa, Asia, and the Middle East at Refugees International, when food rations were previously cut in 2023, malnutrition and gender-based violence increased. Malnutrition rates continue to rise, with the number of children requiring emergency treatment for severe acute malnutrition surging by 27 percent in February 2025 compared to the same period in 2024.

does not extend to supplies to boil and cook the rice, including fuel and cooking oil. Rohingya refugees were “barely surviving” with the existing monthly food rations, according to the RRRC of Bangladesh, and if rations were to be cut further, it would have a devastating impact on refugee health, nutrition and safety – particularly for women and children, who make up 78 percent of the population. Moreover, according to Daniel Sullivan, the director for Africa, Asia, and the Middle East at Refugees International, when food rations were previously cut in 2023, malnutrition and gender-based violence increased. Malnutrition rates continue to rise, with the number of children requiring emergency treatment for severe acute malnutrition surging by 27 percent in February 2025 compared to the same period in 2024.

Class Difference and Economic Disparity

A growing class difference and economic disparity has emerged within the camp, creating unequal access to goods and services. Due to their lack of legal status in Bangladesh, Rohingya refugees do not have access to the formal financial system. Rohingya refugees increasingly rely on remittances from a relative in a third country that are sent through informal systems of money transfer, such as Hawala and Hundi, and mobile-based banking platforms like bKash, illegally bypassing formal channels. While aid agencies provide essential rations using the e-voucher system, the prohibition on cash distribution means that those without external financial assistance lack purchasing power and are unable to supplement aid rations with other necessities. Women, especially widows, single mothers and new arrivals, are especially impacted by this disparity.

Economic inequality in the camps has several negative implications:

- Rise in Informal and Risky Economic Activities: Some refugees engage in high-risk informal labor or exploitative activities to access cash, particularly women, children and those without strong male family networks. These circumstances also incentivize refugees to flee on dangerous boats to other countries, or fall into the trap of human traffickers.

- Potential for Exploitation: Refugees with access to cash can leverage economic power over others, leading to unequal bargaining dynamics, debt cycles and exploitation of labor within the camp.

- Increased Social Tensions: Those without financial support feel a growing sense of frustration and resentment toward those who can afford additional goods.

- Unequal Access to Nutrition: Those with cash can buy fresh food, meat and vegetables, while the poorest families rely on limited rations, leading to worsening malnutrition for children.

Survey Data and Analysis

Insufficient Rations and Essential Supplies

Respondents and interviewees highlighted the insufficiency of their monthly rations, which fail to meet basic food needs and provide essential supplies. They described what they can afford with their ration e-voucher is limited to rice, lentils, oil and salt, with no vegetables and a notable lack of protein. Many expressed that the food is inadequate to feed their families, with some mentioning a reduction in their rations since their arrival in 2017. We clearly observed signs of malnutrition among the children in the camps, such as skeletons showing, distended stomachs and hair loss.

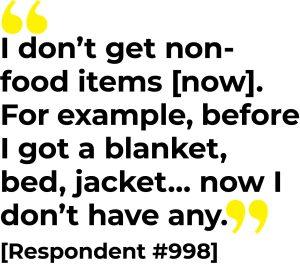

Interviewees also highlighted the lack of non-food items, such as clothing or hygiene products, in their ration distributions. Some mentioned that they received soap and fuel from an NGO, but it was a one-time item. A woman in Camp 5 shared that she received a small supply of sanitary pads six months prior, which was insufficient for her needs. Interviewees mentioned that blankets or winter kits have also not been distributed since they first arrived. One respondent stated, “I don’t get non-food items [now]. For example, before I got a blanket, bed, jacket, etc. in the winter, but now I don’t have any non-food items” (Respondent # 998).

Interviewees highlighted the challenge of not being able to afford dowry for their daughters, as they are entirely dependent on aid with no source of income. Though prohibited in Islam, dowry is a common practice in Rohingya culture; a 2019 study showed that 79 percent of marriages in the Rohingya camps in Bangladesh entailed giving a dowry. One interviewee in Camp 12, married with seven children, shared that one of her daughters migrated to Malaysia a year and a half ago because they could not afford her dowry. She went to Malaysia, married a Rohingya man there, and they have a child. Since they lack refugee status in Malaysia, however, they live in hiding and continue to struggle. Mothers and young single women who we interviewed in Camp 12 expressed similar concerns about not having enough money to pay the dowry for their daughters. A mother of two daughters in camp 1E says that the culture of dowry and the cost of marriages is an impediment to marriages, which is a major stressor in their lives.

entirely dependent on aid with no source of income. Though prohibited in Islam, dowry is a common practice in Rohingya culture; a 2019 study showed that 79 percent of marriages in the Rohingya camps in Bangladesh entailed giving a dowry. One interviewee in Camp 12, married with seven children, shared that one of her daughters migrated to Malaysia a year and a half ago because they could not afford her dowry. She went to Malaysia, married a Rohingya man there, and they have a child. Since they lack refugee status in Malaysia, however, they live in hiding and continue to struggle. Mothers and young single women who we interviewed in Camp 12 expressed similar concerns about not having enough money to pay the dowry for their daughters. A mother of two daughters in camp 1E says that the culture of dowry and the cost of marriages is an impediment to marriages, which is a major stressor in their lives.

The existence of private shops inside the camps highlights the paradox of a controlled economy—those with cash can access better food, clothing and other essential goods, while others remain fully dependent on aid distributions that do not always meet their needs. This is reflected in the clothing of the women we interviewed, some dressed in quality abayas (full-length outer garment) and others in mismatched donations. Those who worked had access to diapers for their families while other children went without. One woman who had a job at an NGO and a brother overseas had an actual bed – the only bed we saw in the shelters.

Challenges Collecting Aid as a Woman

Women who do not have a male relative to collect their rations face challenges in picking it up themselves from distribution centers, where there are mostly men. Interviewees reported that aid supplies are sometimes intercepted by armed groups. One interviewee in Camp 5 reported that her brother-in-law’s son was stabbed by a gang member after leaving the distribution center with his family’s ration. In an interview with the wife of an imam in Camp 1, she highlighted the significant challenges Rohingya women face when collecting aid or rations. Many women have expressed distress over the difficulties of navigating crowded distribution sites, where they often feel unsafe and vulnerable. The situation is particularly dire for elderly and sick women, who struggle with the physical demands of standing in long lines and competing for limited resources. These women are frequently mistreated and looked down upon by service providers, who dismiss them as “low-class people.”

Young and single women, in particular, are subjected to harassment in these public spaces, further deterring them from accessing essential aid. The lack of gender-sensitive distribution mechanisms exacerbates their vulnerability, forcing many to rely on male relatives or intermediaries, which can expose them to further risks of exploitation. The combination of social stigma, physical hardship and gender-based harassment underscores the urgent need for more dignified, accessible and protective aid distribution systems that prioritize the safety and well-being of Rohingya women.

Women commonly reported a lack of coordination among NGOs and the use of outdated data, leading to unequal ration distribution across the camps. One respondent noted, “Misunderstanding or lack of awareness of local customs and needs can lead to ineffective aid distribution” (Respondent # 982).

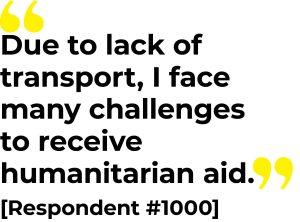

Additionally, those residing farther from distribution points face significant challenges in transporting their rations back to their shelters. “Due to lack of transport, I face many challenges to receive humanitarian aid from a distribution point” (Respondent # 1000).

Additionally, those residing farther from distribution points face significant challenges in transporting their rations back to their shelters. “Due to lack of transport, I face many challenges to receive humanitarian aid from a distribution point” (Respondent # 1000).

Some respondents noted that service providers exhibit preferential treatment, often treating those living closer and more familiar to them better, while mistreating or neglecting those from distant areas.

Recommendations Addressing Food

The suspension of USAID funding has severely disrupted food assistance programs, leaving Rohingya refugees with fewer resources, rising malnutrition rates and increasing economic disparities. While rice distributions continue, the lack of cooking essentials, declining nutrition programs and the manipulation of the e-voucher system have made food insecurity one of the most urgent challenges facing the Rohingya population. Without immediate intervention, the current food crisis risks escalating into a full-scale humanitarian catastrophe.

Recommendations for the U.S. Government

Given its historical leadership in human rights and refugee protection, the U.S. must take concrete actions to uphold its commitments and provide meaningful support for Rohingya refugees.

The recent freeze on U.S. funding for Rohingya refugees has placed hundreds of thousands at risk of starvation and malnutrition. As the largest historical donor to Rohingya refugee programs, the U.S. must:

- Unfreeze, Restore and Increase Aid: Reverse the current suspension of foreign aid to ensure that life-saving food assistance is reinstated for Rohingya refugees.

- Commit to Predictable, Multi-Year Funding: Establish stable and long-term financial commitments to humanitarian organizations operating in Rohingya camps. This approach will prevent future disruptions and enable effective planning and implementation of aid programs.

- Work with WFP and IOM to ensure funds are efficiently allocated to the most urgent needs.

Avoid funding organizations that operate under the military Junta’s influence or support the Junta, and instead include cross-border, grassroots and local groups as funding recipients to ensure resources are reaching those most in need.

Recommendations for the Canadian Government

Given its historical leadership on this issue, Canada must take concrete actions to advance its track record and provide meaningful support for Rohingya refugees, including:

- Increase Humanitarian Aid to Rohingya Refugees: Funding levels should be restored to previous levels and increased to meet the dire needs of the Rohingya.

- Commit to Predictable, Multi-Year Funding: With the absence of a multi-year strategy, the amount of aid allocated for the Rohingya is reduced.

- Coordinate with USAID, WFP, and IOM to ensure funds are efficiently allocated to the most urgent needs.

- Avoid funding organizations that operate under the military Junta’s influence or support the Junta, and instead include cross-border, grassroots and local groups as funding recipients to ensure resources are reaching those most in need.

Recommendations for U.N. agencies

- Address Funding Cuts: UNHCR should host a stakeholder meeting in Cox’s Bazar with NGOs and CSOs, involving both current and former participants in Rohingya refugee assistance programs, with the objective of mobilizing international donors to increase financial commitments for humanitarian efforts.

- Improve Aid Distribution by:

- Enhancing coordination efforts to ensure data is not outdated.

- Creating an oversight process to ensure that refugees who live at a greater distance from aid distribution centers receive equal treatment in collecting aid.

- Creating a separate distribution system for women without a male relative. Work with mosques to help with this.

Recommendations for Rohingya Imams and their Wives

- Provide general education about the Islamic requirements about marriage and dowries, in which it is the man who is meant to give the wife a dowry mahr, and not the other way around. This should alleviate the burden on families with respect to their daughters.

- Provide general education around the mahr and that it need not be a burdensome amount.

Chapter Two: Education

Background

The 1982 Burmese Citizenship Law profoundly affected Rohingya access to formal education in Burma by stripping them of citizenship and excluding them from state-run institutions. Without legal status, Rohingya children were systematically denied entry into government schools, leading to widespread educational disenfranchisement. Over the decades, the Burmese government’s restrictions intensified, leading to bureaucratic barriers, school closures and outright bans on higher education for Rohingya students.

Educational Exclusion and the Rise of Religious Education

In response to these systemic exclusions, the Rohingya community turned to religious education through madrasas (Islamic schools). These institutions became the primary source of learning, not only providing religious instruction but also fundamental literacy and numeracy skills. Madrasas also played a crucial role in providing women with access to religious education, who, like others, were systematically denied access to formal schooling. As the Burmese government continued to deny Rohingya participation in public education, madrasas became the only structured education option available, fostering community cohesion and preserving cultural identity. This is the reason most Rohingya women who are educated in the camps are alimahs (female Islamic scholars).

This reliance on madrasas for education persisted even after many Rohingya fled to Bangladesh. In the Cox’s Bazar refugee camps, where formal schooling remains limited and NGO-run learning centers provide only basic education, madrasas continue to function as the main educational institutions for many Rohingya children. Studies indicate that in the absence of a recognized curriculum, many Rohingya prefer religious schools over NGO-run centers, as they offer a sense of continuity and community cohesion. Among out-of-school children in the camps, 44 percent attend madrasas, a significantly higher rate compared to other educational options. However, because madrasa education is not officially recognized by the Bangladeshi government, Rohingya children lack formal certifications, further restricting their future prospects.

Prior to 2017, Bangladesh had quietly admitted some Rohingya refugee children into local schools. Following the mass influx of refugees from Burma in 2017, however, the Bangladeshi government pressured educators to expel the students on the grounds of national security. Bangladesh’s Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commission (RRRC) instructed headmasters “to monitor strictly so that no Rohingya children can take education outside the camps or elsewhere in Bangladesh.” A policy was set in December 2017 by Bangladesh’s National Task Force on Rohingya issues, led by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that Rohingya children who arrived after August 2017 are only permitted to receive informal education in the camps in the Burmese language based on Burmese curriculum, and were not allowed to learn the Bangla language. The idea was that the Rohingya children would soon return to Burma so there was no need for formal education; however, the violence in Burma persists more than eight years later. So that kind of temporary solution is no longer adequate. Access to education is a right enshrined in international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Articles 22, 28 and 29) that Bangladesh ratified in 1990; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Articles 13 and 14), which Bangladesh ratified in 1998; and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 26).

Eventually, the RRRC chief informally permitted UNHCR to introduce an unofficial English-language curriculum for registered refugee children within the camps, though this initiative only extended to class 8 and lacked formal policy support. Meanwhile, Burmese authorities refused to approve use of the “Myanmar national curriculum” for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, preventing these children from receiving certifications or taking national examinations. In November 2021, UNICEF launched the Myanmar Curriculum Pilot to provide Rohingya children with education based on the Myanmar curriculum up to age 14, to help prepare them for their return to Burma. Human Rights Watch observed, however, that none of these children “have access to certified, formal primary or secondary education, or to university or college” and it was unclear whether the pilot program would be formally accredited or be scalable to reach the over 400,000 other children in need.

The combination of legal exclusion in Burma and restrictive educational policies in Bangladesh has created a profound educational crisis for the Rohingya, with a third generation of Rohingya now being raised without access to certified education. An educated Rohingya benefits Burma if they return, strengthens Bangladesh if they remain and empowers themself in all circumstances.

Compounding the educational crisis further is funding cuts, as well as stipulations by the U.S. Department of State on programs receiving aid to remove any mention of “girls,” “women,” “youth,” “equity,” or “inclusion,” making it nearly impossible for NGOs to continue their educational programs that target women because of high dropout rates.

Survey Data and Analysis

Community-Led Schools Strongly Preferred Over NGO-Run Learning Centers

The community of women we surveyed expressed an overwhelming preference for community-led schools compared to NGO-run learning centers. Of the surveyed mothers who provided a response to the question on which school provided a better education (720), 77 percent believed that community-led schools (Rohingya-run) offer a better education, while 23 percent felt that NGO-run learning centers are superior. This highlights how many parents trust their community’s own schools to educate their children effectively. While others appreciate the formal structure and resources of NGO centers, the preference for community-led schools runs counter to assumptions that NGO-run education is automatically viewed as more legitimate or higher quality. Most of the critical feedback about education quality came from parents whose children attend NGO-run learning centers, reflecting deep community frustration with the limitations of NGO-run centers, which is explored further below.

With regards to the responses, it is important to note that the numbers refer to mothers, not individual children. A household was counted if at least one child was enrolled in the respective school type. Some women have multiple children in different schools, and some households reported that their children were too old, out of school or never enrolled. Therefore, these totals do not imply universal schooling across all 1,000 households surveyed. In fact, based on qualitative responses, many households are excluded from this count because their children are now adults or had no access to education at all.

Widespread Uncertainty About Whether Children Are Receiving Adequate Education

Despite the expressed preferences, when asked about their overall satisfaction with their children’s education, most respondents answered that they were “not sure.” Only 1 in 3 women (37 percent) of the 535 who responded to the question on satisfaction felt confidence that their children were receiving the education they need to succeed. A majority (57 percent) indicated they are uncertain. A small minority (6 percent) gave a firm “No,” but combined with the “Not Sure” responses, this data suggests that over 60 percent of respondents lack educational confidence. This uncertainty about their satisfaction is evident across both groups (those whose children attend NGO schools and those in community-led schools). For example, even some who chose NGO learning centers as “better” voiced that the education is still not adequate. Conversely, others in community-led programs also felt their children are not learning enough to secure a good future, as their education is “not formally recognized.” This widespread uncertainty is just as serious as outright dissatisfaction, and it represents a key opportunity for policy and programmatic improvement.

Key Concerns Raised

Mothers provided valuable feedback explaining why they felt the education system is not delivering. Several common concerns emerged:

- No Path to Higher Education: A frequent worry was the lack of formal recognition and advancement. Parents note that after attending camp schools, children “will not have any certificate and no chance to step for higher education” (Respondent #12). In other words, even if their kids finish the available classes, they cannot progress to higher grades or obtain recognized qualifications. This makes parents feel the current schooling may be a dead end in terms of future opportunities.

- Limited Curriculum and Low Quality Teaching:

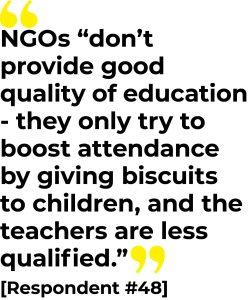

Many parents questioned the quality of what is being taught. Some criticized the NGO learning centers for focusing more on enrollment numbers than learning outcomes. For instance, one parent complained that NGOs “don’t provide good quality of education – they only try to boost attendance by giving biscuits to children, and the teachers are less qualified” (Respondent #48). Another complained their child remained “in the same lesson for months.” This suggests that teaching quality and curriculum depth are seen as poor. In community-led schools, while parents appreciate the initiative and preservation of culture and language, there are concerns about limited resources and informal teaching methods. Overall, parents fear their children are not learning enough skills or content to truly succeed.

Many parents questioned the quality of what is being taught. Some criticized the NGO learning centers for focusing more on enrollment numbers than learning outcomes. For instance, one parent complained that NGOs “don’t provide good quality of education – they only try to boost attendance by giving biscuits to children, and the teachers are less qualified” (Respondent #48). Another complained their child remained “in the same lesson for months.” This suggests that teaching quality and curriculum depth are seen as poor. In community-led schools, while parents appreciate the initiative and preservation of culture and language, there are concerns about limited resources and informal teaching methods. Overall, parents fear their children are not learning enough skills or content to truly succeed.

In addition, some respondents and interviewees felt the curriculum in the learning centers does not align with the needs of the Rohingya community – compared to the community-led schools – and also expressed a need for Rohingya teachers:

“Since community led schools are initiated by Rohingya teachers they try to provide good quality of education with the Burmese curriculum and follow the educational system of Myanmar, therefore we feel like our children are now studying like the children used to study in Myanmar. Also the Rohingya teacher always cares for the development of the young generation” (Respondent #12).

While parents whose kids attend only madrasa are generally content, (nearly all of the madrasa-only parents answered that their children’s education needs are being met, about 88 percent affirmative in this small group), they recognize its limitations in academic content. Even though madrasa-only households are generally satisfied, they still acknowledge the superiority of secular schooling.  This underscores a demand among the refugee community for greater access to quality formal education, as many feel that the available learning centers, while better than nothing, still fall short of what their children need to truly succeed.

This underscores a demand among the refugee community for greater access to quality formal education, as many feel that the available learning centers, while better than nothing, still fall short of what their children need to truly succeed.

- Access and Continuity Issues: Another concern is that not all children can attend school consistently. Some respondents pointed out that their children were unable to attend any school due to various reasons, such as overcrowding, distance or being too old for the available classes. Especially for older kids or those who arrived after 2017, options are very limited. Parents who answered “No” to getting needed education often cited that their child simply has no access to regular schooling or can only go to basic literacy classes. This inconsistent access adds to the feeling that the education system is failing many families entirely.

- Resource Constraints: Both NGO and community-run schools face resource issues. Parents mentioned shortages of trained teachers, educational materials and appropriate facilities. For community-led schools, in particular, everything is informal – classes might be held in cramped shelters with volunteer teachers. NGO centers, while more structured, still have large class sizes and limited grades. These resource gaps leave parents concerned that their children are not receiving the depth and breadth of education they need.

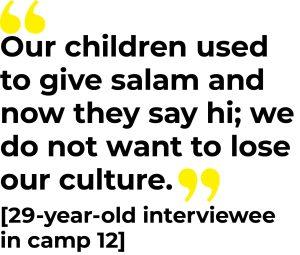

- Cultural Relevance:.

Madrasas also appear to address the concern that some interviewees complained of, which is the changes in culture because of the influence of non-Muslim NGOs. A 29-year-old mother in Camp 12 said, “Our children used to give salam and now they say hi; we do not want to lose our culture.”

Madrasas also appear to address the concern that some interviewees complained of, which is the changes in culture because of the influence of non-Muslim NGOs. A 29-year-old mother in Camp 12 said, “Our children used to give salam and now they say hi; we do not want to lose our culture.” - Language of Instruction: As a Muslim country, Bangladesh understands the norms of Rohingya Muslims, but there were issues related to the language of instruction. One 14-year-old Rohingya girl we interviewed in Camp 5 expressed that in her school, “The English teacher is a local Bangladeshi. I cannot understand him because he uses Bangla language. I need a Rohingya teacher for the English language.”

In summary, survey responses and our interviews highlight that community-led (Rohingya-run) education is more trusted than NGO-run learning centers among Rohingya families. A majority of surveyed mothers who have children in school chose community-led schools over NGO-run learning centers. Whether NGO or community run, however, most families are unsure or unconvinced that the current education systems are equipping their children for the future. They are concerned about their children losing critical years of learning while growing up in the camps and lacking future prospects. There is greater satisfaction with madrasas that allow them to preserve religious identity, while acknowledging its shortcomings in providing formal education. Key issues include the lack of higher-grade schooling or certification, doubts about teaching quality and the fact that many children cannot access a full education.

Education for Rohingya Women

Several survey respondents emphasized the lack of educational opportunities for women when they age-out:

- “As a woman, I have no way to learn anything useful in the camp.”

- “We are willing to study but there is no opportunity for girls and women.”

- “Give women a chance to have education so that they can make income in the future.”

Respondents noted limited and outdated skills programs available to women. They sought women-only madrasas. Interviewees explained that, due to cultural customs, they or their daughters stopped going to school once they reached maturity (upon their first menstrual period).

One important aspect of the madrasa system is its role in providing women with access to religious education. Unlike formal education, which has been systematically denied to Rohingya girls, madrasas have remained a space where women can study and gain knowledge, even on reaching maturity. This has allowed the emergence of women scholars, particularly wives of imams, who play a crucial role in community organization and leadership. These women serve as trusted figures to whom Rohingya women in the camps can relay their concerns, especially when they are unable to approach majhis (community leaders) or imams directly. Their influence extends beyond education, as they often mediate disputes, advocate for women’s needs and organize community-based initiatives. Their role as both educators and organizers highlights the importance of expanding access to learning for Rohingya women and integrating them into broader community decision-making structures.

Recommendations Addressing Education

As new generations grow up stateless and in exile, the absence of accredited education poses a significant challenge to Rohingya self-sufficiency and possible integration into other countries. Addressing this issue requires international efforts to expand formal education opportunities while respecting the community’s cultural and religious identity. Ensuring that Rohingya children receive a well-rounded education—combining religious instruction with practical skills—will be crucial in breaking the cycle of exclusion and dependency. Insights from the survey and interviews highlight an urgent desire for improvements – such as formal recognition, expanding curriculum, improving teacher training and creating pathways for students to continue their studies beyond the basics.

Recommendations to Bangladesh Interim Government and to the Minister of Education:

Bangladesh must first be appreciated for hosting over 1 million Rohingya, as well as appointing a special advisor for Rohingya issues. Despite not being a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, Bangladesh is bound by fundamental international human rights obligations that protect refugees from harm and uphold their dignity. The treatment of Rohingya refugees, particularly women and children, must align with Bangladesh’s commitments under international law. We call on the Bangladesh government to:

-

- Lift Restrictions on Rohingya Education: Allow full educational opportunities for Rohingya refugees by removing all restrictions to their instruction levels, choice of language and curriculum.

- Implement a Certification System: Develop an accredited certification system for all levels, allowing Rohingya children to pursue education with meaningful outcomes, enabling them to transition to higher education or employment opportunities.

- Allow Additional Support for Community-led Schools: Allow donor funds to support community-led schools, not just learning centers.

Recommendations for UN Agencies (i.e. UNICEF) and NGOs focused on Education:

- Allocate Funding to Community-Run Schools: Redirect resources towards training Rohingya teachers, developing curricula and building better learning facilities for community-led schools and religious schools (madrasas). Ensure sufficient educational materials, classrooms and infrastructure.

- Develop a Higher Education Pipeline: Work with international partners and universities to provide scholarships, remote learning options and advance training. Provide a certification system through private universities.

- Enhance Vocational Training Programs: Integrate sewing, computer skills, handicrafts, carpentry, technology and language training into the community-run school system. Teach Rohingya to repair plumbing, electrical equipment, gas stoves, solar panels and how to build infrastructure in the camp.

- Strengthen Community-Governed Education Boards and Empower Parents: Establish a local education board composed of Rohingya teachers, community leaders and parents to oversee school operations and maintain accountability. Establish parent-teacher committees to address concerns and improve educational conditions.

- Support Female Organizing and Leadership: Support female scholars to educate their community and include them into broader community decision-making structures.

Chapter Three: Security

Background

Rohingya women fled genocide in Burma, only to face a new threat in the camps in Bangladesh from gangs and armed resistance groups, who operate with impunity. Gangs, such as the Munna Gang, and armed resistance organizations, such as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) and the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO), are involved in kidnapping for ransom, forcibly recruiting children, forcing women into marriage, committing murder, trafficking people and smuggling drugs.

ARSA membership in the camps grew rapidly as they claimed to be leading an ethno-nationalist fight for the rights of Rohingya, but they also forcibly recruited members using violence and threats. Rohingya refugees refer to ARSA as “the night government” because it is at night that they enforce their authority through threats, abductions,and killings, spreading fear and terror among the Rohingya in the camps.

RSO is one of the oldest Rohingya armed groups; both ARSA and RSO have been vying for power after the 2021 military coup d’état in Burma. In the past, ARSA and RSO were engaged in armed conflict opposing the Myanmar military; however, reports suggest that their allegiances have shifted to allying with the Myanmar junta to counter the Buddhist Arakan Army, which has and continues to commit abuses against Rohingya civilians.

Since 2021, ARSA, RSO and other armed resistance groups have violently clashed in the camps, resulting in increased instability compounded by lack of protection for refugees. Bangladesh’s Ministry of Defence of Bangladesh has stated that there are at least 11 armed resistance groups in the camps; some began as ARSA but split off into new groups, others committed abuses claiming to be ARSA that were not, in fact, commanded by ARSA.

Rohingya face challenges accessing justice primarily due to their lack of legal status and distrust of authorities handling security concerns. When a complaint is made, generally the majhi is the first to be contacted, who arranges a gathering of community leaders to make a decision; if it is deemed “unresolvable,” it is forwarded to the CiCs. If the aggrieved person is not satisfied, they can contact the local police station or army or request CiCs file a formal complaint, but this would be an exceptional case. Masjid communities play an important role in conflicts involving personal law. Corruption is the most cited challenge to accessing justice using this informal justice-seeking process. There is also a lack of female representation in the mediation process.

Compounding further the security issues for Rohingya women and girls in particular is the impact of funding shortfalls, which increases vulnerability to exploitation, trafficking and gender-based violence, and may force many to resort to desperate measures, such as embarking on dangerous boat journeys to find safety.

ya students.

Survey Data and Analysis

Safety was a concern across all the women interviewed, no matter their marital status. Safety-related concerns – such as crime, violence, security, or danger – were mentioned in the survey responses of 92 percent of single women, 95 percent of married women, and 93 percent of divorced and widowed women. Of the camps that were surveyed, the highest incidents related to safety were reported in Camp 1E, Camp 5 and Camp 12. Women highlighted safety concerns related to threats and exploitation by criminal gangs and armed groups, lack of private toilets, inadequate lighting on the pathways, risk of robbery, and fear of gender-based violence and trafficking.

Rise in Crime by Gangs and Armed Resistance Groups

Interviewees who arrived in the camps in 2017 reported that after a few years, gangs began forming, leading to an increase in criminal activity. Many interviewees described hearing frequent gunfire at night and witnessing murders even in daylight involving random community members. They described the fear their children feel that when new people come to the camp, it is a gang member. Robbery has increased in the camps; with bamboo shelters that are easy to break into, women and their families are left vulnerable. Interviewees in Camp 5 reported witnessing robbery by gang members.

Husbands and Male Relatives: Kidnapping, Forced Recruitment, Threats

Rohingya women are not only victims of gender-based violence themselves, but are also left vulnerable when their male relatives – particularly their husbands and sons – are targeted by gangs and the authorities. As one respondent noted, “I am safe somehow but my son and husband are totally unsafe inside the camp due to gang groups” (Respondent #20).

Women reported that their husbands were kidnapped and held for ransom. Young men traveling between camps are also at risk of abduction. If a husband was kidnapped, the wife had to arrange the ransom, often selling jewelry and possessions or borrowing money. After the husband’s return, repaying debts became an overwhelming challenge, as most men could not find work. In some cases, husbands never return. A married interviewee in Camp 15 says that “we had a different trauma in Burma and a different one here. Here, criminals take our husbands and our futures.” The number of Rohingya trying to escape Bangladesh by boat has risen 74 percent since October 2023, according to a report by University of New South Wales; increasing lawlessness in the camps is one of the major push factors.

Several women in Camp 5, ages 21, 22 and 23, reported that their husbands had to go into hiding because they refused gang recruitment. As a result, their husbands were beaten and threatened. These women also receive direct threats from gang members regarding the whereabouts of their male relatives. One interviewee’s brother-in-law was forcibly recruited and remains missing, and another’s brother-in-law’s son was stabbed by a gang member while returning from collecting his ration at a distribution center. Many mothers fear for their sons’ safety and struggle with sleepless nights due to the constant threat of recruitment and violence.

Children: Kidnapping, Forced Recruitment, Threats

The abduction of children has instilled deep fear and mistrust within the Rohingya refugee camps, exacerbating an already fragile social fabric. A Rohingya woman residing in Camp 1E shared her concerns, stating, “We can’t even trust our own community.”

The abduction of children has instilled deep fear and mistrust within the Rohingya refugee camps, exacerbating an already fragile social fabric. A Rohingya woman residing in Camp 1E shared her concerns, stating, “We can’t even trust our own community.”

One case involved a 10-year-old Rohingya child who was lured away by another young boy under the pretense of playing. His parents were later contacted by the kidnappers and demanded to pay a ransom of 200,000 Bangladeshi Takas (about $USD 1,645) for his release. In another instance, a child was abducted by a vegetable vendor who enticed him by saying, “Baby, come to me, I will give you chocolate.”

Another growing concern among Rohingya families is the recruitment of young men into armed groups, with many fearing a direct pipeline between local gangs and militant factions such as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) and other armed organizations. Mothers of male teenagers and young adults express deep anxiety that their children may be coerced or feel compelled to join these groups due to financial desperation, intimidation or promises of protection. Reports indicate that some young men are forced to pay to join, while others are lured in through social pressures or threats. A mother of two in Camp 1E says that “we are worried. We heard 70 youths were sent to Burma and only 5 are alive.” The lack of economic opportunities, coupled with deteriorating security conditions in the camps, has made young Rohingya particularly vulnerable to recruitment. This growing trend further erodes trust within the community and heightens the risks of violence, exploitation and external retaliation, underscoring the urgent need for targeted interventions to provide Rohingya youth with alternative opportunities and safeguard them from forced or exploitative enlistment.

A 35-year-old widowed interviewee in Camp 12 shared that her son fled to Malaysia two years ago after gangs threatened him while he was in school. She stated that threats against young boys to join the gangs are common. In Malaysia, her son continues to struggle without legal refugee status.

Another 35-year-old married interviewee in Camp 12 reported that her 12-year-old son was kidnapped by a gang member a month and a half before the interview. He was taken to Sittwe, Burma, and forced to work for the gang. The gang member demanded a ransom of 20,000 Takas (about $USD 165) for her son’s return and threatened to kidnap her 14-year-old daughter. Unable to pay, she sold bamboo and borrowed from relatives and neighbors.

“I escaped from Myanmar to Bangladesh because our houses were burned down by the Myanmar military and Arakan army. I also lost all my properties in Myanmar. I crossed the border and a big sea to save my children’s life and my life. But after being here, one of my sons was kidnapped by gang members. I am appealing to the international community to seek justice for my son. Being a mother, I cannot handle this kind of horrible stress. I am very depressed for my son. It is better to kill me before my children. I just want back my son (sic), nothing else. We just escaped Burma to get peace for my kids. Is there any justice for these kinds of cases? I am seeking justice for my son” (interviewee, Camp 12, 35-years-old, married).

Forced Marriage and Human Trafficking

Young Rohingya women face severe threats, including forced marriage, human trafficking and confinement due to fear of abduction. Several interviewees shared that brokers visit parents with proposals from outside, enticing them with low cost weddings without dowry. One 23-year-old married interviewee shared that her 22-year-old sister in law was sent to India, where she was arrested by the Indian government. She is still in a detention camp. She said that young women are often sold in Jammu, India to non-Muslim men. An 18-year-old unmarried woman from Camp 5 recounted how, at the age of 16, a gang member persistently called and pressured her to marry him. When she refused, he threatened to kill her father and brother. Despite changing her phone number, he continued to track her down. She did not know how he obtained her contact information or where he lived. In a desperate attempt to escape, she turned to a Rohingya broker who promised to help her leave the country. Instead, she was trafficked to Indonesia, where she had to pay a ransom of more than 500,000 Bangladeshi Takas (about $USD 4,105) to get back to Bangladesh. Upon arrival, she was arrested and deported to Burma, where she was imprisoned for five months.

The prevalence of human trafficking in the Rohingya camps is alarming. According to our survey data, 30 percent of respondents reported knowing of cases where women were forced into unsafe situations, including human trafficking, sexual exploitation and forced labor. One respondent stated, “I know a girl from my camp who was taken forcibly by someone and handed over to a local man who again kept her as a laborer. Many months later, she could escape from there (sic)” (Respondent # 18). Many trafficking routes involve initial transportation to Teknaf, approximately 40 kilometers from the camps. There, kidnappers wait in hilly areas near the border, intercepting Rohingya travelers and demanding ransom before releasing them.

The prevalence of human trafficking in the Rohingya camps is alarming. According to our survey data, 30 percent of respondents reported knowing of cases where women were forced into unsafe situations, including human trafficking, sexual exploitation and forced labor. One respondent stated, “I know a girl from my camp who was taken forcibly by someone and handed over to a local man who again kept her as a laborer. Many months later, she could escape from there (sic)” (Respondent # 18). Many trafficking routes involve initial transportation to Teknaf, approximately 40 kilometers from the camps. There, kidnappers wait in hilly areas near the border, intercepting Rohingya travelers and demanding ransom before releasing them.

For many young, unmarried Rohingya women, daily life is marked by severe restrictions and fear. Many report feeling suffocated, unable to leave their shelters except for essential trips to the latrines or medical facilities. “We feel upset because we can’t go anywhere,” one young woman shared. “It’s a mental prison,” said an 18-year-old girl in Camp 1, who is unmarried and yearning for an education. Stories of girls being sold in Malaysia, subjected to torture and traded from one trafficker to another have instilled deep fear, leaving many young women trapped in a cycle of isolation and vulnerability. The lack of protection, coupled with the impunity of traffickers and criminal networks, highlights the urgent need for comprehensive intervention to address the crisis of gender-based violence and exploitation in the camps.

For many young, unmarried Rohingya women, daily life is marked by severe restrictions and fear. Many report feeling suffocated, unable to leave their shelters except for essential trips to the latrines or medical facilities. “We feel upset because we can’t go anywhere,” one young woman shared. “It’s a mental prison,” said an 18-year-old girl in Camp 1, who is unmarried and yearning for an education. Stories of girls being sold in Malaysia, subjected to torture and traded from one trafficker to another have instilled deep fear, leaving many young women trapped in a cycle of isolation and vulnerability. The lack of protection, coupled with the impunity of traffickers and criminal networks, highlights the urgent need for comprehensive intervention to address the crisis of gender-based violence and exploitation in the camps.

Safety Concerns Using Sanitation Facilities

Rohingya refugee women face significant challenges in accessing sanitation facilities due to safety concerns, cultural norms and overcrowding. Many avoid using toilets during the day to maintain privacy and prevent exposure to men, while at night, the lack of adequate lighting and security heightens the risk of harassment and assault. One interviewee from Camp 5, age 22, shared that she refrains from eating or drinking much at night to avoid going to the toilet. Another interviewee from Camp 5, age 13, mentioned that her friend was sexually harassed by a gang member on her way to use the toilet.